A Warning To Myself and My Generation in Regard to Ironic Detachment and Trying Too Hard

I decided to transcribe from Douglas Rushkoff's book, Coercion, a significant passage that enlightened me, and I believe it will feel familiar to many people I know, and with many people with whom I've discussed advertising, generational ennui, etc.

I've taken the liberty of adding images and commentary (added parenthetically) in order to break up the rather long excerpt, because while our senses and attention spans are used to such lengths within the bindings of books, I believe Internet reading lends itself to brevity, abbreviations and blurbs. Medium is the message, right?

Oh, and I made bold some of my favorite sentences and whatnot.

From Coercion:

Media-savvy television viewers pride themselves on their ability to watch programming from the safe distance of their own ironic detachment. Young people delight in watching "Melrose Place" in groups so they can make fun of the characters and their values by talking back to the screen throughout the show. Others turn to shows like "Beavis and Butthead," whose characters' constant commentary on the MTV videos they watch serves as built-in distancing device. (Consider also Mystery Science Theater) The wisecracks keep the audience emotionally removed from the seductive charms of the images on the screen.

In addition to using icons, marketers have come to recognize the way irony makes a wary viewer feel safe, and now they regularly employ irony in the commercials targeted at these more difficult demographic groups. "Wink" advertising acknowledges the cynical stance of resistant viewers: Sprite commercials satirize the values espoused by "cool" brands, sometimes even parodying their competitors' obvious image-based tactics, and then go on to insist, "Image is nothing. Thirst is everything." A brand of shoes called Simple developed a magazine campaign with the copy "Advertisement: blah blah blah...name of company."![]()

(In Hebrew!)

By letting the audience in on the hollowness of the marketing process, advertisers hope to be rewarded by the appreciative viewer. Energizer batteries launched a television campaign where a fake commercial for another product would be interrupted by the pink bunny marching across the screen. The audience was rescued from the bad commercial by the battery company's tiny mascot. The message: The Energizer bunny can keep going, even in a world of relentless hype.

Of course marketers haven't really surrendered anything. What's really going on here is a new style of marketing through exclusivity. Advertisers know that their relationship prides itself on being able to deconstruct and understand the coercive tactics of television commercials. By winking at the audience, the advertiser is acknowledging that there's someone special out there - someone smart enough not to be fooled by the traditional tricks of the influence professional. If you're smart enough to get the joke, then you're smart enough to know or buy our product.

Like all advertisements, these self-conscious commercials help the viewer define his own identity. The strategy is not as overt as showing Michael Jordan in a pair of Nikes so that young athletes will identify with their hero. Instead, a person's notion of "self" is defined by how sophisticated he feels in relation to the images on his TV set. If he has grown up deluged by coercive advertising and expended effort to break free, then he will identify himself as a media-savvy individual. Wink advertising gives him a chance to confirm his own intelligence.

In the advertising wars between long-distance carriers, underdog MCI attempted to show how they were friendly and perky, especially compared to industry leader AT&T. A beautiful young operator mischeviously whispered to us that AT&T doesn't want their customers to hear about MCI's low rates, or their discount Friends & Family plan. She ridiculed AT&T's ads begging people to "come home," and implied that they revealed Ma Bell's desperation. AT&T fought back with their own ads, highlighting the coercive nature of MCI's marketing: that people were fooled into writing lists of their friends and relatives so that MCI could make annoying phone calls trying to enlist them. The advertisements were no longer about quality or service. They were about the advertising campaigns themselves.

Wink advertisements very often borrow imagery from another company's advertisements as a way of eliciting viewer approval. After Lexus made the ball bearing famous by rolling it seductively over the precision engineered lines of its luxury sedan, Nissan did the same thing in their ad to demonstrate how a much less expensive car could exhibit the same qualities. BMW sought to rise above the whole affair, demonstrating their car's unmatched turning radius by putting the whole vehicle through the same tight turns as the ball bearing went through in the other brands' meaningless test. Finally, in an erreverent spoof of the automobile advertising wars, Roy Rogers rolled a ball bearing around the edge of a roast beef sandwich. Get it? Wink wink.

In a similar campaign, Levi's made fun of Calvin Klein's heroin-chic, ultra-skinny supermodels. The company pictured healthy models wearing Levi's under the caption, "Our models can beat up their models."

As the techniques of self-consciousness and parody become more recognizable and, accordingly, less effective, advertisers have been forced to go yet a step further, taking the media reflexivity of advertising into the realm of the nonsensical. It's as if by overwhelming us with irony, they hope to blow out the circuits we use to make critical judgments.

The Diesel jeans company ran a series of billboard and magazine ads designed to critique the whole discipline of advertising. One showed a sexy but downtrodden young couple, dressed in stylish jeans and arguing with each other in what looked like the messy, 1960s-era kitchen of a dysfunctional white-trash family. The ad meant to reaveal the illusory quality of the hip retor fashion exploited by other advertisers. Diesel would not try to convince anyone that those were the "good old days." We were meant to identify with the proposition that the enlightened values of the sixties, as represented by the media, are a crock. But the meaning is never made explicit. Another Diesel campaign consisted of advertisements which themselves were photos of garish billboards placed in ridiculous locations. One showed a sexy young couple, dressed in Diesel jeans, in an advertisement for an imported brand of ice cream. The billboard, however, was pictured in a dirty, crowded neighborhood filled with poor Communist Chinese workers.

(At bottom of ad: "protest, support and act..." But for what? I briefly visited diesel.com, but quickly had to leave before I became enraged. They had, of course, something about global warming and how they were "Global Warming Ready." Ok, I thought, that's good. But again, how are they ready? The answer: With scantily-clad Asian women. Obviously! Take that Al Gore! I knew something was missing from An Inconvenient Truth - hot sluts. See, there's a huge image of a sexy couple cooling off on top of a skyscraper while beneath them, water from what apparently are melted glaciers, has risen to nearly half the height of the city's other buildings. Oh, and the hot babe is pouring water into the dude's mouth, while his shirt is unbuttoned to help him cool off. So, despite the apocalyptic tableau in the ad, we're relieved to discover that in order to combat drastic climate change, we need not practice restraint in energy use or encourage creative technology solutions. Instead, we just have to be sexy enough to be comfortable with taking our shirt off, and charming enough to attract an aesthetically pleasing mate to pour water over our body.)

Benetton and The Body Shop ran similar ads, but at least theirs made some sense. One Benetton campaign pictured Queen Elizabeth as a black woman and Michael Jackson as a caucasion to comment on racial prejudice. A series of Body Shop ads featuring giant photos of marijuana leaves, presumably to call attention to drug and agriculture laws. These are appeals to a target market that feels hip for agreeing with the sentiments expressed and for grasping the underlying logic. There is, indeed, something to "get."

We are supposed to believe that Diesel's ads also make sociopolitical statements, but we never know quite what they are. In fact, the ads work in a highly sophisticated disassociative way: They make us feel as tense and uneasy as we do after a good scary story - but we refuse to admit to our anxiety lest we reveal we are not media-savvy enough to get the joke. The campaign is designed to lead the audience to the conclusion that they understand the ironic gesture, while the irony is left intentionally unclear. No one is meant to get the joke. In that moment of conufusion - like the car buyer subjected to dissociative hypnotic technique - the consumer absorbs the image within the image: two sexy kids in Diesel jeans. Thinking of yourself as hip enough to "get" it - no matter what "it" may be - means being susceptible to lying to yourself, and to being programmed as a result.

That's all coercion really is, after all: convincing a person to lie to himself by any means necessary. The stance of ironic detachment, while great for protecting ourselves from straightforward linear stories and associations, nonetheless makes us vulnerable to more sophisticated forms of influence. After a while, even a detached person begins to long for a sense of meaning or some value, any value, to accept completely and genuinely. In spite of their well-publicized cynicism, so-called Generation Xers reveal in numerous studies that they often feel lost and without purpose. Disillusioned with role models, the political process, and media hype, they are nonetheless seeing something to believe in.

(I am reminded here, of course, of Fight Club, and Tyler Durden's: "Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don't need. We're the middle children of history, man. No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our Great War's a spiritual war... our Great Depression is our lives. We've all been raised on television to believe that one day we'd all be millionaires, and movie gods, and rock stars. But we won't. And we're slowly learning that fact. And we're very, very pissed off.")

As people search for a sense of authenticity in their increasingly disconnected "virtual" experience, advertisers seize on the opportunity to help us delude ourselves into thinking we haven't really lost touch. A shrewd advertisement for an airphone service shows a businessman stuck on a jet flight while his young daugter dances in a recital at her elementary school. He has foregone his family obligations in the name of business. But in the airphone commercial, he calls his daughter from the plance after her recital, and, basked in golden light, she is as delighted to hear his telephonic voice as she would have been to see him in the flesh. The television viewer who is searching for meaning in his life will accept the faulty premise of the advertisement: that the airplane telephone can actually connect him with a life he has left behind.

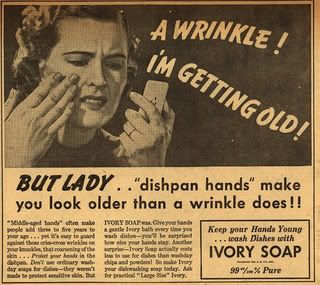

The back-to-basics authenticity of such advertisements capitalizes on a growing sense that we are no longer in touch with who we really are. In the past, advertisers worked to generate this sense of disconnection. In the 1950s and 1960s, a marketer would present an image, personality, or story with which we were meant to identify, and then stretch that image in order to make us feel unworthy, to give us something to aspire to: The girl in the hair-color advertisement looks just like me - when I was twenty years younger and five shades less gray; the woman in the commercial has a dirty kitchen and noisy children just like me...but she is confident enough in her rug cleaner to throw a dinner party for her husband's business partners that night. The viewer identified with the character, only to be made to feel unworthy in comparison.

Today, however, a deep sense of disconnection and unworthiness is just the starting point for the detached viewer. As a result, the opposite effect takes place: We welcome the opportunity to let down our guard, even for a moment. Having grown to resent all the striving toward the ideals represented in commercials, we yearn to get off the treadmill of yearning altogether. We yearn not to yearn - to be still and content. To just be.

The newest approach to the antiyearning urge capitalizes on these feelings. The Calvin Klein CK Be perfume advertisements offer the media-fatigued sophisticate a chance to relax and literally "just be." Uniquely beautiful and detached-looking young people stare confidently into the lens. Beneath them are captions like "Be hot. Be cool. Just be." The slogans in companion ads all stress that people should have the ability to express their individuality and be who they really are. "CK Be fragrane is about who you are...it's about the freedom to express your individuality...it's about the freedom to be yourself."

The astonishing supposition of these ads is that the young audience for whom they are intended does not feel they already have permission to just be. Unlike the models in the advertisements, who appear to have earned their cool resolve by draining the life out of themselves through dedicated heroin abuse, the audience must expend effort to maintain a sense of self against the onslaught of commercials and other coercive messages. The CK Be ads suggest that if we just buy one thing - a single bottle of perfume - we can finally be who we really are with no further effort.

Like all of the image-based advertising that went before it, the CK campaign once again capitalizes on its audience's undetermined sense of self. A person who is striving not to strive is striving nonetheless - perhaps even more desperately than those who are simply yearning for a better lifestyle. Our aspiration toward a simpler, less taxing way of relating to the world around us makes us no less vulnerable to the suggestions of others on how best to get there. Being "in" is a booby prize, since it depends on a false and further self-defeating claim to exclusivity. The emergence of a protective, ironic stance, though temporarily immunizing, only contributes to our longing for ways to feel genuine and connected - and will likely turn out to be just one more chapter in the greater narrative of the history of advertising.

No comments:

Post a Comment